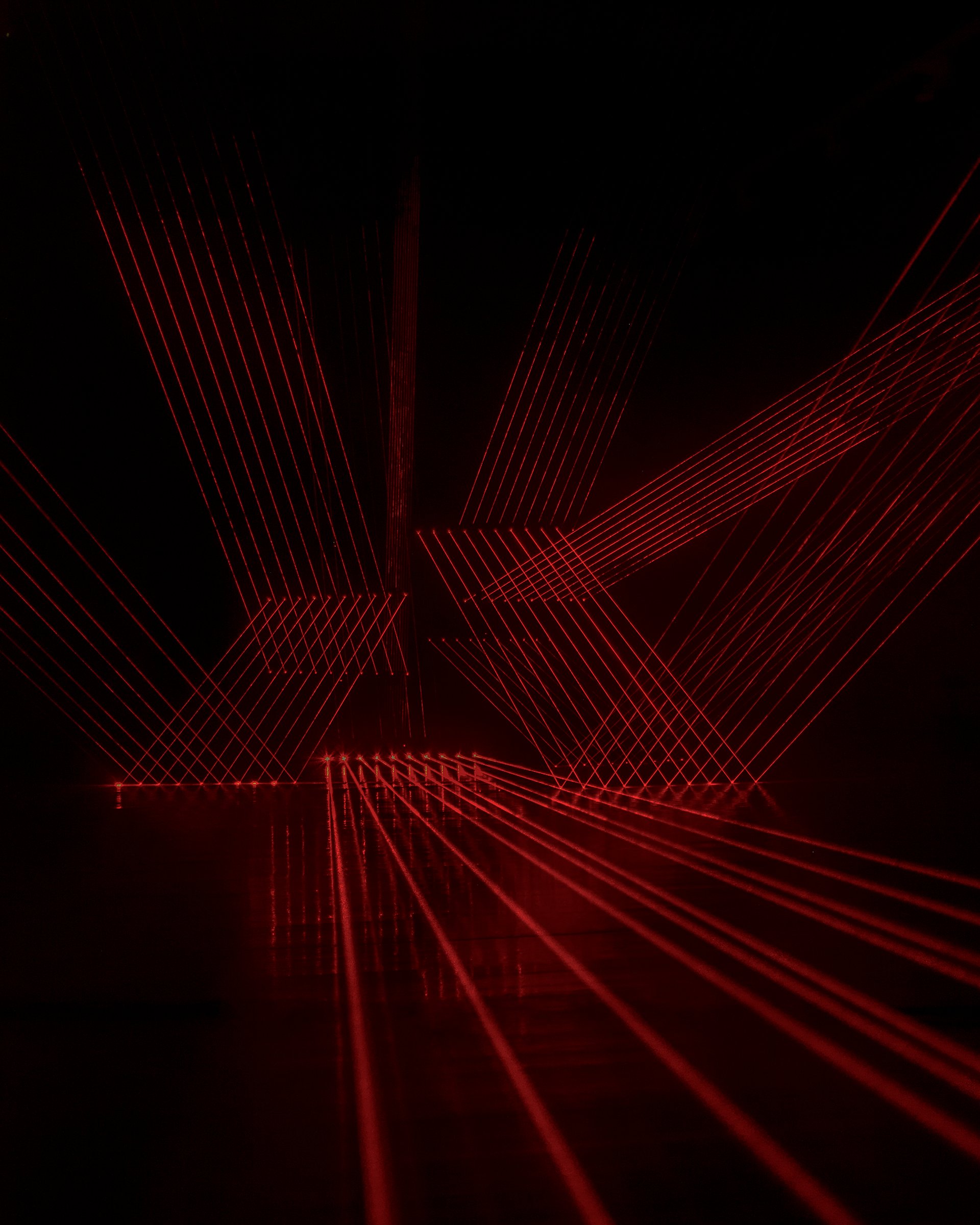

Cover photo: Ethereal Natures. Courtesy Radiante Light Art Studio

Balancing art and technology, Radiante Light Art Studio was founded in Valencia in 2014 and, in just over a decade, has become an international reference point for exploring light as a sensorial and phenomenological language. Under the direction of Manuel Conde, the studio investigates the relationship between perception, space, and consciousness, creating experiences in which light serves as both a material and a narrative medium.

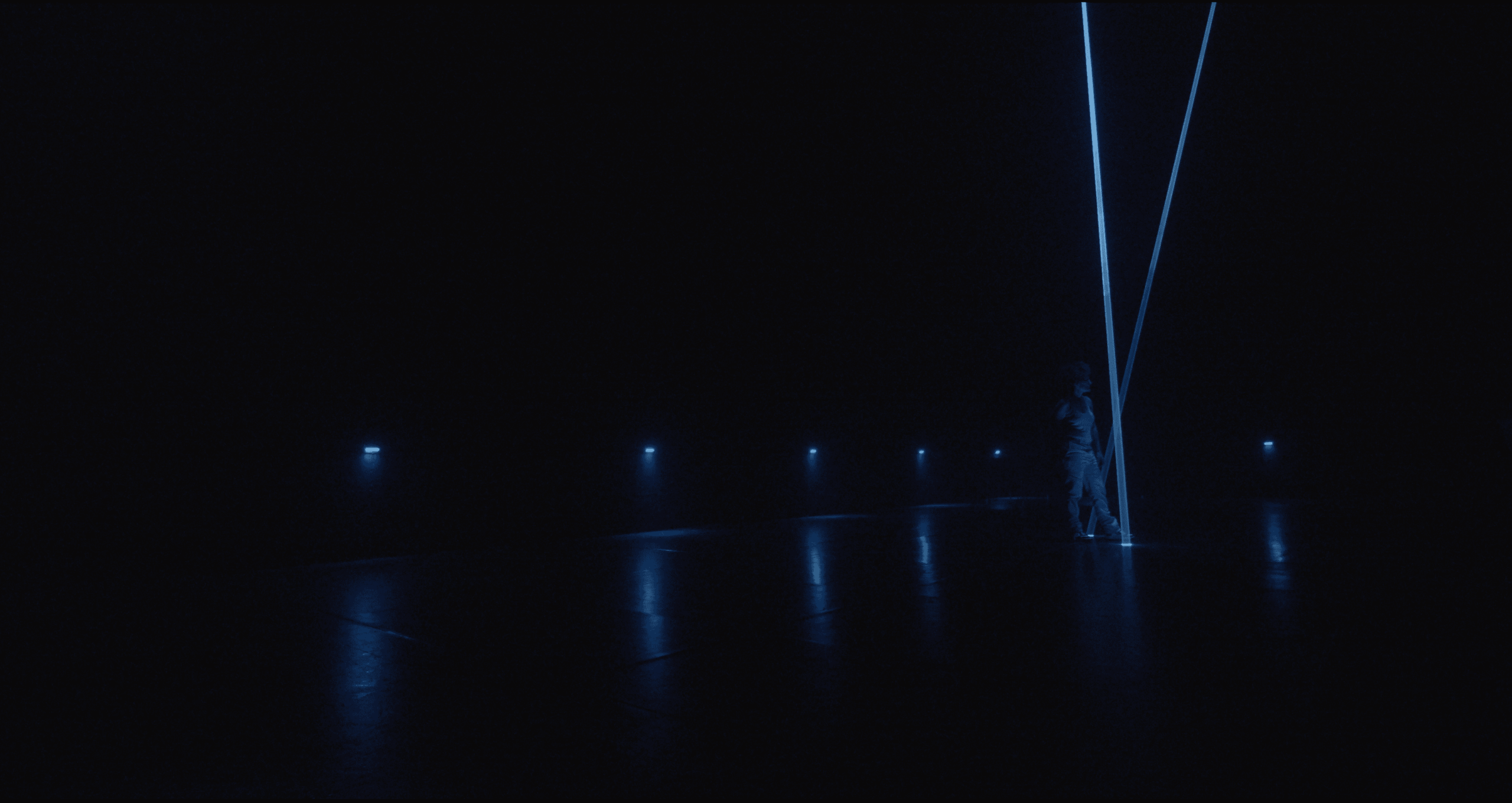

From this vision emerges a hybrid creative language: through video, pixel, and laser mapping, sound design, and luminous sculpture, Radiante constructs environments where light, sound, and space interact in real time, transforming the observer into an active part of the creative process.

From site-specific installations like Worlds of Light to the recent Cartografía de un Rayo, presented at the Volumens Festival 2025, Radiante dissolves the boundaries between the physical and the digital, inviting viewers to become co-authors of the work.

In this interview, Manuel Conde explains the studio’s cross-disciplinary approach, the importance of how individuals experience their work, and the ongoing search to balance science, emotions, and space. The studio operates as a creative lab, using light to inspire thought and movement and to imagine new worlds.

Radiante uses light not only as an aesthetic medium but also as a tool to convey emotions and complex ideas. How does it transform space and shape the viewer’s perception?

«In my work, this happens through preliminary analysis, intuition, and a clear intention. Everything can be instrumentalized to transmit and alter perception: we study how people perceive things, their cultural references, and their expectations. It’s a chimera, of course, but rather than a goal, this model becomes a guide. With this information, we can shape light — playing with atmosphere, form, color, and intensity — to guide the viewer toward states that connect with their inner world.»

You use lasers, augmented reality, and interactive digital systems. How does technology transform immersive experience and the audience’s relationship with the work?

«Since the immersive Photorama created by the Lumière brothers in 1920, art has evolved: first with moving images, then interactivity, accessible technology, real-time generation, and now artificial intelligence. These tools make it easier to create immersive experiences, but they have two consequences: more ideas and more “trash.” The audience, instead, redefines its role: it seeks immersion, connection, and sometimes narcissistic gratification. The biggest revolution lies in how people have been educated to relate to art. To sum it up: technology rarely determines what we imagine; first we decide what we want to create, then we find the best way to make it real.»

Your installations often induce altered perceptual states, inviting the viewer to experience light as a physical presence. What is the intention behind this approach, and what emotional impact does it have?

«The intention is never singular. Some works have a purely aesthetic purpose; others seek direct bodily interaction with light and space. One constant element is the use of light as a sculptural and architectural material, capable of shaping space and altering perception. The audience is extremely diverse: mood, background, and context influence the degree of connection. This is why we remain present during exhibitions, observing reactions that become valuable insights for continually refining our creative choices.»

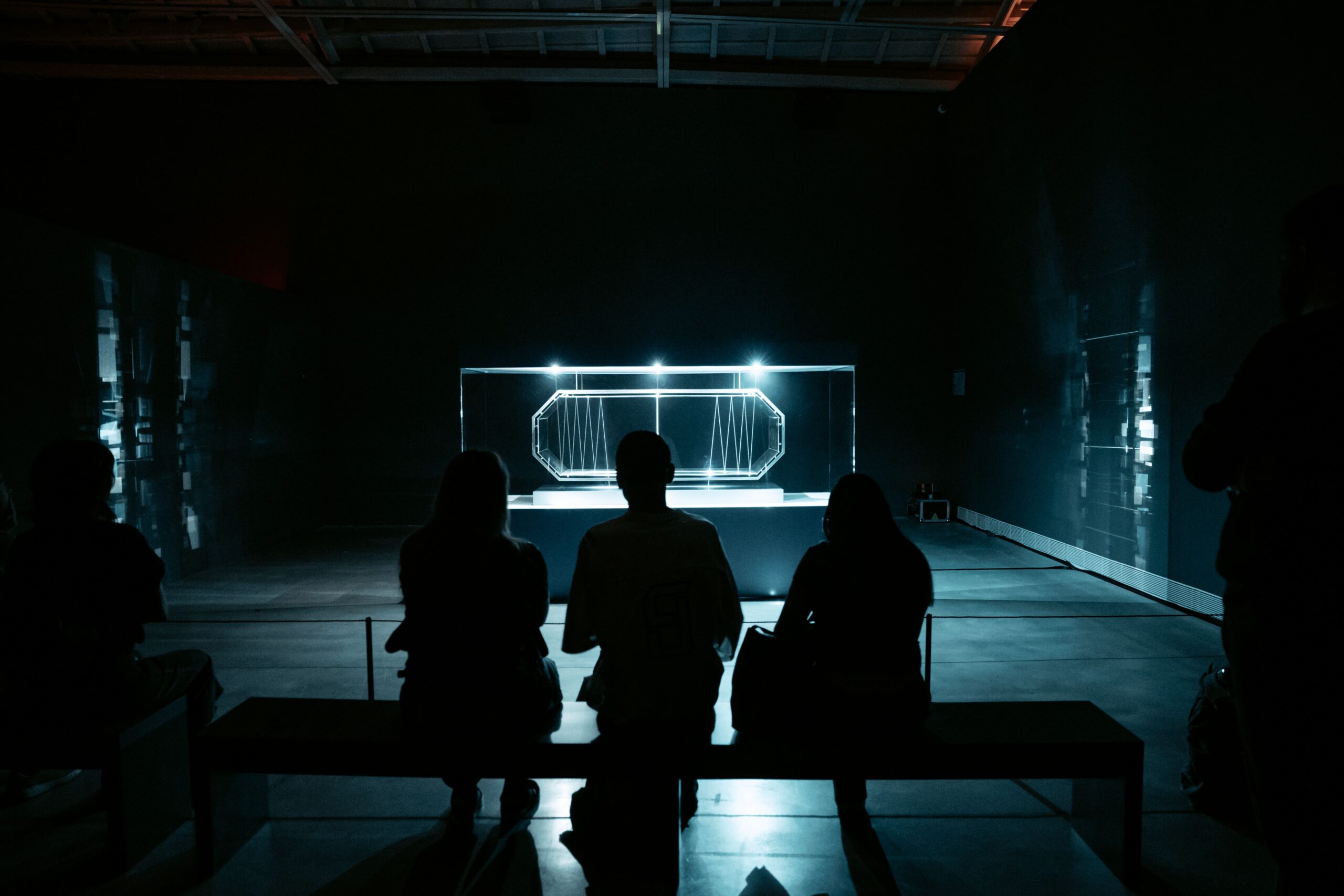

Cartografía de un Rayo, presented at Volumens Festival (Valencia, 2025), explores the relationship between light, matter, and the digital world. What does this installation represent for you?

«Cartografía de un Rayo explores how form shapes light and generates new light in return. The work exists in two dimensions: a physical sculpture and its digital twin, which reflects and amplifies its behavior. We’re interested in the contrast between these levels: the digital, where rules are few and limits are defined by sensors, and the physical, influenced by an endless array of variables. This contrast synthesizes our exploration of the boundary between material perception and the virtual dimension.»

In your works, music, architecture, and performance merge into a multisensory language. What role do interdisciplinary collaborations play in your creative process?

«Collaborations are essential for Radiante Light Art Studio. Our core is small, but we surround ourselves with professionals and artists — some from the two-dimensional field (graphic design, motion graphics), others from the three-dimensional (architecture, 3D), technical specialists, and materialization experts. Initial divergences are valued and often lead to natural convergence. With external partners, two identities meet: we begin without assumptions, through improvisation sessions — sonic, visual, luminous, poetic, or choreographic — to find points of contact. Then we analyze the experience, define the conceptual framework, and each person reworks it through their own identity. One example is Ruido Blanco, with Luna y Panorama: the synergy radically shaped the final result and allowed us to inhabit emotional deregulation while maintaining balance.»

In Worlds of Light, at Centro Botín in Santander and at Bright Festival in Florence, audience interaction becomes integral to the work. How does this reflect your idea of “participatory light”?

«Worlds of Light is a site-specific luminous sculpture composed of red laser beams. We draw on collective references: viewers perceive the device and feel invited to participate. By moving and interrupting the beams, they modulate the work and create new compositions in real time. We start from an initial composition as a frame of reference; the piece becomes complete through dialogue with those who move through it. In this way, ‘participatory light’ becomes co-authorship: the work is not simply contemplated, it is built with the body and with presence.»

Your artistic path is grounded in an empirical investigation of light and space. Can light-based art expand our perception of reality?

«Yes, but not uniformly. We want to reassign meaning to space, often perceived intuitively by the audience. We start from established perceptual patterns to introduce breaks that shift sensory habits or induce specific emotional states. Some works speak to the mind, but most are perceived by the body before they are understood through words. To grasp them fully, one must listen to the body and stay connected to physical sensations.»