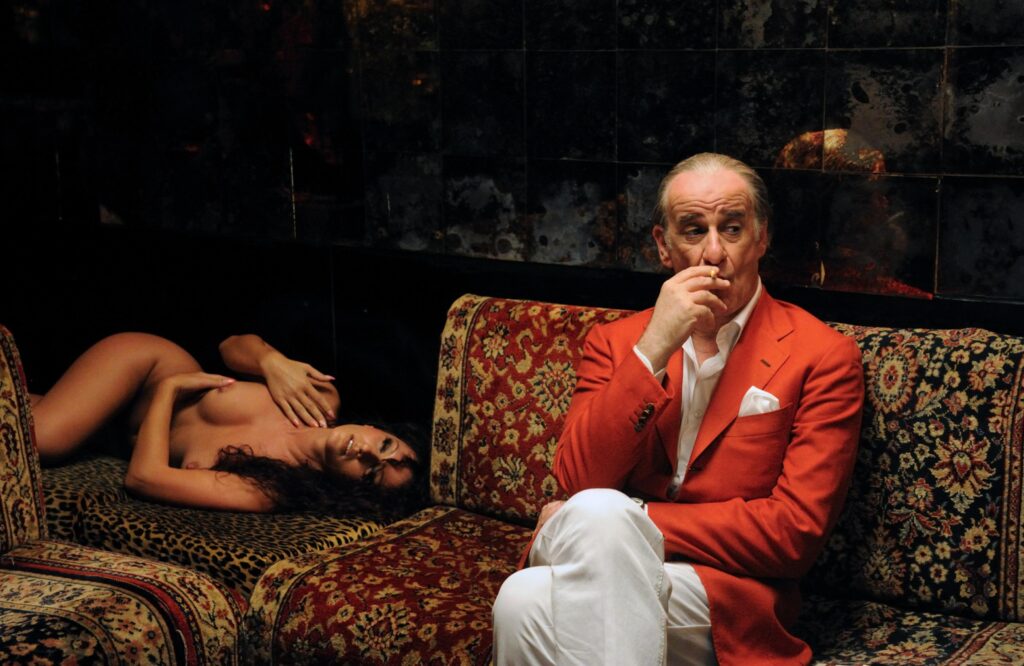

Cover photo: The Young Pope, HBO / SKY Atlantic

If Paolo Sorrentino’s cinema has further “dolcevitized” Italy in the eyes of the world—for many, the country is now a composite of Renaissance art, angels, fluorescent-colored food, and breathtaking sunsets or dawns—it is largely thanks to the construction of his tableaux and to an “obsessive cinematography” that, working through baroque excess and an extreme contrast between over- and underexposure, lends Sorrentino’s worlds a mystical, quasi-religious aura.

But why, in The Great Beauty and in other films or series such as The Young Pope and The New Pope, does light reflect a divine ontology while the men and women of the story remain immersed in the murky squalor of everyday life? The Neapolitan director—deeply enamored with violent contrasts and Dionysian excess—treats the scene with obsessive care, particularly the synoptic balance between light and shadow, precisely to bring human misery to the surface.

With his latest film, La Grazia, as well as with The Hand of God and Parthenope, Sorrentino makes a significant shift: he entrusts cinematography to the more naturalistic approach of Daria D’Antonio, abandoning the opalescent flair of Luca Bigazzi. Why? Most likely because he needed to. The light in La Grazia is far more linear and lacks the epiphanic emphasis of earlier films. Instead, it reveals itself as a more intimate inward turn—one that extends The Hand of Godwhile breaking with Sorrentino’s baroque tradition. But this is another story, or rather, a point of synthesis that reinforces the director’s long and complex relationship with cinematography—a relationship that, after his early films, reaches a moment of profound revelation with The Great Beauty.

The Great Beauty: Rome’s luminous epiphany

The professional love story between Paolo Sorrentino and cinematographer Luca Bigazzi reaches its apex in the pop and visionary Rome of The Great Beauty, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2014.

In an interview with Anec Lazio, Bigazzi recounts how Sorrentino, together with the screenplay of what would become a major masterpiece about Italy’s early-2000s decadence, also handed him a photograph taken at dawn at the Imperial Forums. In doing so, the director laid the foundations of the film’s mood without ever having to explain it.

«[The photograph was] taken at dawn, with frost after a night of rain,» Bigazzi explained. «With that image, Paolo was suggesting a magical, slightly dreamlike visual aura—very elegant—that would later stand in stark contrast to the squalor of the characters.»

That frosty, enchanted early-morning light was a true epiphany, guiding the two professionals in their search for an optically striking environment, one born from luminous inhomogeneity in favor of depth, volumes, and shadow.

The use of the Pro-Mist filter for a “pre-dawn” cinematography

In the same interview, Bigazzi explains that, in agreement with Sorrentino, they used an ’80s–’90s Pro-Mist filter, composed of countless tiny irregular particles designed to “veil” the image—as if seen through a stocking—and to exaggerate highlights. In other words, a technical device that allowed the magical Roman dawn light to be translated into every frame of the film.

«The Pro-Mist filter is an extreme enhancer of luminosity. In the film, all the lamps have a halo of opalescence. The extreme overexposure and, at the same time, the darkness are very evident in certain scenes,» the cinematographer explains. This is why Sorrentino’s Rome takes on a dreamlike dimension, channeling La Dolce Vita–era Marcello Mastroianni through a contemporary palette.

Youth: a glacial light, like purgatory

From Rome as a laboratory for divine light, the journey moves to the Swiss Alps of Youth, which become an incubator for a glacial, purgatorial light. The lighting of the luxury resort emphasizes whites and the aquatic greens of the pools, creating a powdery, muffled limbo that feels like the threshold separating life from death.

Even in the mountains, however, Sorrentino and Bigazzi insist on stark contrasts—between scenes of dazzling beauty, such as the Miss Universe figure in the pool, and raw images of decaying bodies and sagging skin. This is a purgatorial light, suspended between alpine paradise and the hell of certainty. The divine status always looms, but it emerges through confrontation with the human condition.

The Young Pope: the dark sacrality of power

Pop-inflected and deeply chiaroscuro, Paolo Sorrentino’s Vatican—inhabited by Jude Law, cigarettes, manicured hedges, and Cherry Coke—is where Bigazzi delivers his “theological light.” As analyzed in the academic article God Smiles: The Rhythm of Revelation in Sorrentino’s The Young Pope, published in the journal Religions in 2021, Sorrentino chooses a light that “reveals by concealing” to speak of the deus absconditus—the hidden God.

In this iconic series, cinematography and its divine dimension are more evident than in any other work, precisely because the story’s subject is God himself. The most memorable scenes are built around sacred backlighting—such as Pius XIII emerging as a silhouette before blinding windows, like an evangelical apparition. Caravaggio’s influence is unmistakable here, once again revealing its profound impact on the Neapolitan director.

Ultimately, a comparison emerges between Rome and the Vatican: while The Great Beauty celebrates pagan worldliness through light, the Vatican represents spiritual Christian power. Yet under the Roman sky, the cinematography of both stories is united by the same opalescence—almost as if Sorrentino were suggesting that transcendence, whether religious or aesthetic, requires the same dreamlike filter.

Sorrentino Baroque: The Hand of God and Parthenope

“Baroque light” is a term frequently associated with Sorrentino, who uses this style to narrate not only aesthetic but, above all, moral worlds. His most deeply baroque works include The Great Beauty, The Young Pope / The New Pope, and Il Divo—a sharp, political baroque.

With The Hand of God, 1980s Naples is filmed in an almost realist key, with imperfect, domestic light—again by Daria D’Antonio—that sets aside mystical opalescence in favor of a grainy cinematography.

With Parthenope, Sorrentino and D’Antonio return to a fully Mediterranean light: carnal and sensual. Baroque elements re-enter the frame in a less liturgical way, where Caravaggesque influences coexist with a new physicality. The light of Parthenope grazes bodies and structures, transforming the profane into the sacred—as in the sequence in which the protagonist is adorned with the treasures of San Gennaro.

Unlike in the past, this is an affirmative rather than melancholic luminosity: the light of a “woman-city” that fully commands its own shadows.

Opalescent Rome, chiaroscuro Vatican, purgatorial Alps, and carnal Naples: Sorrentino’s light remains both a mystery and a philosophical question. Can beauty redeem human misery? Over thirty years of cinema, the answer has always been the same: no, it cannot. But it can transform it – by illuminating it into a divine spectacle. And perhaps it is precisely in this photographic miracle that the only possible grace can be found.