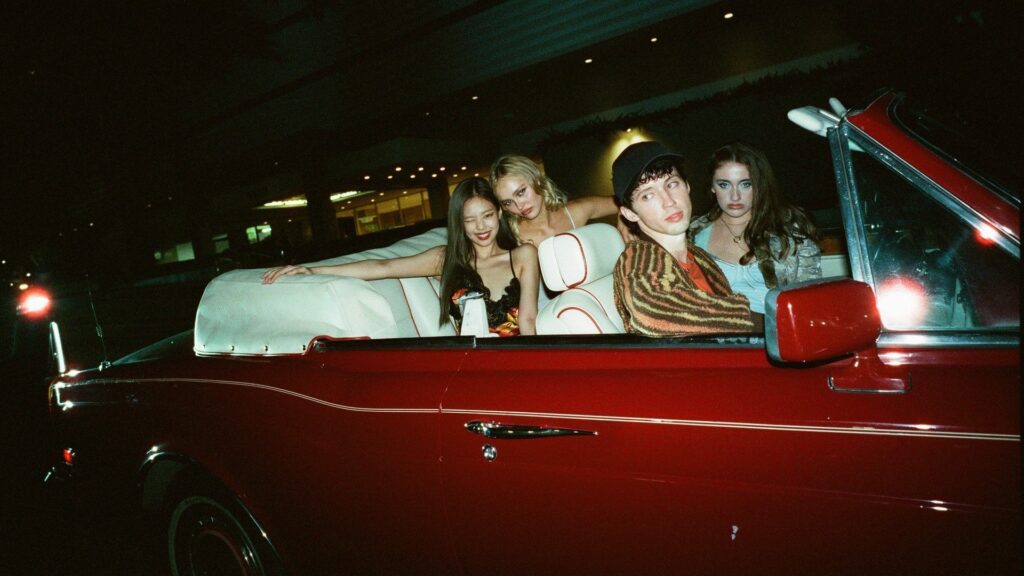

Cover photo: Euphoria. Courtesy HBO

There is a kind of light that doesn’t illuminate, it burns. It’s the visual signature of Sam Levinson, a millennial who chose excess to narrate the trauma of a generation raised inside the digital revolution, always facing glowing screens. In Levinson’s cinema — he is the son of Barry Levinson (Rain Man, Sleepers) and Diana Rhodes, designer and advertising producer — the cinematography is so sharp and violent it almost overtakes the film, flickering over the script.

But this goes beyond style. With Euphoria, Levinson ignited a revolution of taste and consumption: the looks worn by Zendaya or Sydney Sweeney jumped from the screen to New York Fashion Week, in the still carefree pre-Covid world, establishing a new obsessive aesthetic.

Sam Levinson: cinematography or overdose?

Raised among the soft lights of his father Barry’s sets, Sam rejected that narrative warmth early on. If Levinson Senior’s cinema was structure and harmony, Sam’s would be fever and fragmentation.

After debuting with the teen movie Assassination Nation, a cocktail of social media and blood, Levinson revealed his luminous vision of chaos: extreme saturation, pop aesthetics collapsing in on themselves, rebellion filmed as a storm of LEDs. His scenes emerge from a visual field where beauty becomes a symptom of intermittent madness.

Euphoria: the meaning of lights and colors

With the watershed series Euphoria (HBO, 2019), Sam Levinson stopped “shooting” and started composing visions. He does so through a photographic language built on the creative symbiosis between Levinson and Marcell Rév, the Hungarian cinematographer who turned each episode into a glowing polyptych of ecstasy and agony.

It’s impossible not to feel drawn into the radiant embrace of this series — despite its darkness, despite its spirals of loss and depression. Zendaya’s Rue moves like a human prism, her iridescent skin reflecting different colors depending on mood… or substance. In Euphoria, the frame is ruled by a light-drug: psychedelic, obsessive, touched by mysticism. It evokes the same vertigo as the substances Levinson has said he used during adolescence.

The director composes a visionary synoptic table for stories of teenagers haunted by their own demons and by contemporary life. Neon is confession, blue is desire, red is despair. Levinson and Rév build a chromatic grammar where color becomes diagnostic: the temperature of light measures each character’s existential fever.

Even the technical choices are poetic statements: Kodak Ektachrome film, anamorphic lenses that warp depth of field, and hypnotic camera movements turn bodies into painterly surfaces, while the camera chases them, because the gaze, too, is addicted to that blinding light.

Far from any pursuit of realism (or even verisimilitude), Levinson composes a hallucination charged with the euphoria of the (sur)real. A luminous parable telling the story of Gen Z, suspended between selfies and self-destruction.

The Idol: radiant p0rnography and self-destruction

The 2023 series starring Lily-Rose Depp and The Weeknd marks a rupture. Premise: it wasn’t a success and was cancelled after a handful of episodes. Perhaps because Levinson’s aesthetic is so overstated (and overstimulating) it collapses into pure narcissism. Lights, mirrors, reflections — everything saturates until the narrative empties out. In Levinson’s vision, light as addiction is the symptom of an industry that consumes its own idols. The Idol, fittingly, is destined to fail. Perhaps the light in The Idol reaches its saturation point, like a substance pushed beyond safety. It no longer illuminates or burns; it distorts. Scattered spotlights, like needles pressed into skin, push brightness into a pathological form of dependence. The characters — perhaps not explored with enough depth — live in a constant state of needing to be seen, sliding into delirium.

The Idol may simply be too much — especially for the viewer. It’s Levinson’s ultimate overdose, not chemical but aesthetic, where light ends up imprisoning the show itself, which never reached a conclusion, trapped in an eternal present of stagnant visibility.

Malcolm & Marie: the return to black and white

In 2021, Malcolm & Marie was released — a surprising film, the first to be completed during the height of the pandemic, an intimate project that cemented Sam Levinson on Netflix as a filmmaker capable of reinventing himself beyond the serial format. After the chromatic whirlwinds of Euphoria, Levinson makes a radical gesture: he turns off color. The saturated universe gives way to stark black and white, where contrast becomes the aesthetic core.

Inside that California house, two bodies — Zendaya and John David Washington, an actress and her filmmaker boyfriend — become colliding planets reflecting the silent violence of love and ego. Light is no longer revelation but overdose in reverse: chromatic withdrawal that induces vertigo. It’s as if Levinson, between Euphoria and The Idol, before hitting the peak of toxic luminosity, tried to detox with shadows. But does he?

In Malcolm & Marie, lighting slices across faces, heightening the anatomy of each scene like a battlefield between light and darkness. There is no color left to anesthetize the gaze, only the raw tension of who, in turn, dominates and who yields.

Terminal light

Sam Levinson’s light is never innocent. It is the living matter with which he builds and destroys an entire generation. The Gen Z of his stories lives under a spotlight to avoid disappearing, burning with an artificial glow that keeps it alive and consumes it at the same time. In a world where everything must shine — bodies, eyeshadow palettes, pain, even melancholy — Levinson becomes the chronicler of a terminal glow: the one that precedes blackout.

In this tormented way, Sam Levinson delivers the sharpest portrait of our time: a generation that confuses light with life, and overdose with love.