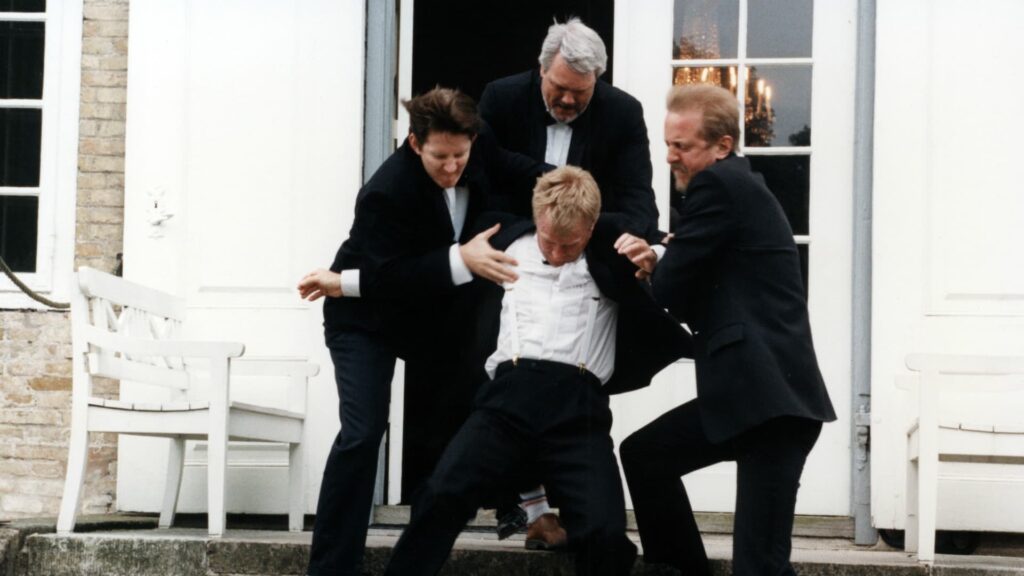

Cover Photo: Mifune, 1999 – Distributed by Scanbox Entertainment

It was the 1990s in Denmark. Two visionary Hamlets—one a Boomer, the other Gen X ignited a cinematic revolution. In just 45 minutes, Danish directors Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg drafted the Dogma 95 Manifesto, also called the “Vow of Chastity.” Their idea? Rebuild a cinema stripped of artificiality: no special effects, no soundtracks, no surreal narratives, and most of all, no artificial light.

Dogma 95 wasn’t just a rebellion—it was an anti-rebellion. A return to the primordial soup of storytelling. An aesthetic closer to the everyday than the cinematic. More radical than Neorealism or the Nouvelle Vague (to which it partly nods, especially Truffaut’s essay Une certaine tendance du cinéma français), Dogma was about capturing a visceral truth through unfiltered visuals. Natural light wasn’t just a rule—it was a visual ethos. It brought the viewer face to face with an unvarnished reality, uncomfortable and real.

Idiots – Dogma #1 and Amateur Light

Idioterne (The Idiots) is Dogma 1—the first official film of the movement. Its plot is chaotic and provocative: a group of young people pretend to be mentally disabled to challenge social norms and provoke unease.

Some critics have compared Dogma to early amateur porn, especially because of its raw lighting. Like in NSFW home videos, the lack of polish becomes a feature—it grounds the viewer in the real. Watching The Idiots feels like seeing a cross between surveillance footage and a VHS recording.

There’s a deliberate carelessness in its composition, color, and light. It’s unflattering and a little bleak. In Spastic Aesthetics – The Idiots, Ove Christensen argues this visual style recalls abstract art, redrawing the line between artist and audience. The film looks like it was shot with a secondhand camcorder on a payment plan.

Von Trier’s crude lighting hits you with its familiarity—harsh, real, and a little sad. It makes you feel both recognized and alienated. We might see ourselves in it, but not how we want to be seen. We imagine our lives bathed in cinematic spotlights—not in the dull overhead glow of a breakfast nook.

Festen – Family Dinner and the Light of Truth

Festen (The Celebration), Dogma 2, directed by Thomas Vinterberg, won the Jury Prize at the 51st Cannes Film Festival. The film is set during a 60th birthday party for Helge, patriarch of the Klingenfeldt family. What starts as a traditional Danish celebration quickly descends into horror when eldest son Christian accuses his father, during the toast, of sexually abusing him and his late sister.

The film’s lighting mirrors the emotional tone. The soft gray daylight filters through clouds. Indoors, the light is Lo-Fi, like an Instagram realism filter. You feel like you’re in the room—wedged between candelabras and polite conversation—when everything shatters.

Festen plays with contrast: day and night, public and private, surface and shadow. It never directs your gaze—it lets the truth spill into the light. Candlelight flickers across faces, revealing not glamour, but damage.

Mifune – Dogma 3 and the Real Light of the Countryside

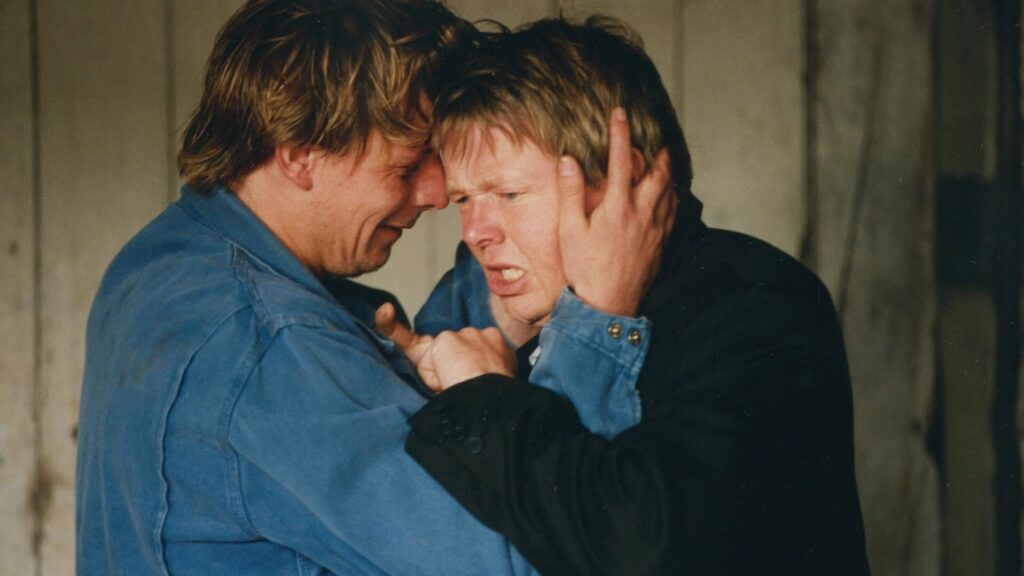

Mifune (Mifunes sidste sang), directed by Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, tells of Kresten, a newlywed who returns to his rural childhood home after his father’s death. He must care for his brother, who has mental disabilities, and reconnect with a rawer, less filtered life.

It’s the most “rural” of the Dogma films. The light is pale, filtered through overcast skies. Interior scenes play with darkness depending on proximity to the windows—light cones, shadows, and dim corners.

These first three films of Dogma 95 aren’t just raw stories—they’re manifestos of how stories can be told. Their use of natural light isn’t nostalgic—it’s defiant. In an era of CGI and synthetic perfection, Dogma reminds us: cinema can still be intimate, flawed, and devastatingly real.