Cover photo: Breath Ghost Blind, exhibition by Maurizio Cattelan at Hangar Bicocca di Milano – ph. Agostino Osio

Pasquale Mari is a central figure in Italy’s theatre and arts scene. He is known for his mastery in lighting design, which he has extended with equal intensity and precision to cinema, opera, and visual arts. Born in Naples in 1959, alongside Mario Martone and Toni Servillo, he co-founded the Falso Movimento collective, which later evolved into Teatri Uniti. His artistic training took shape within the rich and complex Neapolitan theatre scene of the 1980s, where light was not just a technical tool but an actual dramaturgical language.

The experience he gained in this context helped define a working method where technical precision merges with constant visual research.

«Lighting is a daily practice,» Mari often says, «like that of a monk or a stubborn detective,» underscoring the patience and discipline his art demands.

Over the years, Mari has worked closely with his longtime assistant Gianni Bertoli, developing a strong professional bond. His approach hinges on a deep sensitivity to the inner rhythm of the scene, adjusting every lighting change to the dynamics of the action. «The necessary and sufficient light must come from carefully listening to the space,» he explains—revealing just how important it is for him to listen to the environment, even when it’s a backdrop or an artificial setting.

For Mari, light is not just supportive—it’s a design tool that shapes the stage space on par with scenography, gestures, and words. His work stands out for rejecting gratuitous effects: every lighting decision stems from a precise reading of the text and its emotional implications.

«To intercept passing light and turn the stage into a trap that makes it linger before our eyes» is one of his most powerful metaphors, capturing the poetic and visionary essence of his artistic path.

A deep understanding of visual dramaturgy

Mari is an artist who builds images in twilight—balancing matter and abstraction, body and space. His lights don’t illustrate: they create invisible architectures and atmospheres that suspend narrative and heighten perception. The audience is invited to enter environments where light becomes a compositional, narrative, and poetic element. His method, which he describes as that of a lighthunter, is based on a daily observation of lighting conditions and a deep understanding of visual dramaturgy.

This attentive gaze allows him to create true perceptual landscapes, such as Jeanne Dark at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, where precisely cut beams and calibrated color temperatures follow the protagonist through an evolving space, emphasizing tension and introspection. His lighting compositions are never ornamental—they stem from a process of subtraction, where every source is fine-tuned to serve the text, the space, and the temporal flow of the performance.

That’s how he creates highly charged atmospheres with minimal lighting cues, focusing the audience’s attention on a single gesture or facial expression.

A distinctive trait is also found in his collaboration with Arturo Cirillo for The Misanthrope, where the lighting shapes a mental space more than a physical one, exposing the compromises and hypocrisy in Molière’s play.

From theatre to opera: the emotional architecture of the stage

Pasquale Mari has shaped a distinctive visual language in which light becomes scenic thought throughout his career.

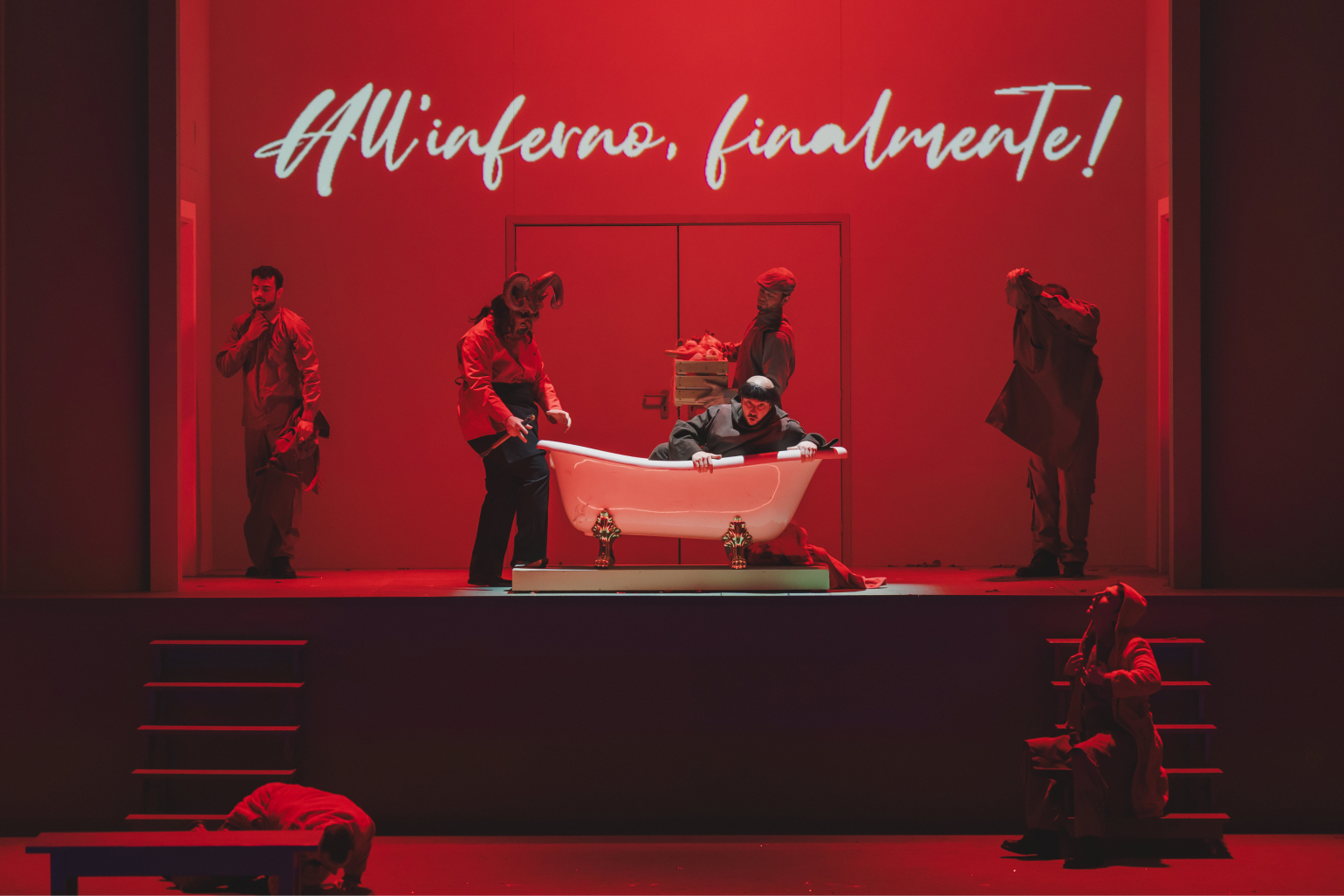

From Italy’s major theatres to the world’s leading opera houses, he has illuminated stages like La Scala in Milan and the Opéra Bastille in Paris, building atmospheres that heighten dramatic tension and reveal the emotional architecture of the scene. In his lighting for Lucia di Lammermoor and Un Ballo in Maschera, light marks the transition between reality and inner projection, as a psychological tool to analyze the character.

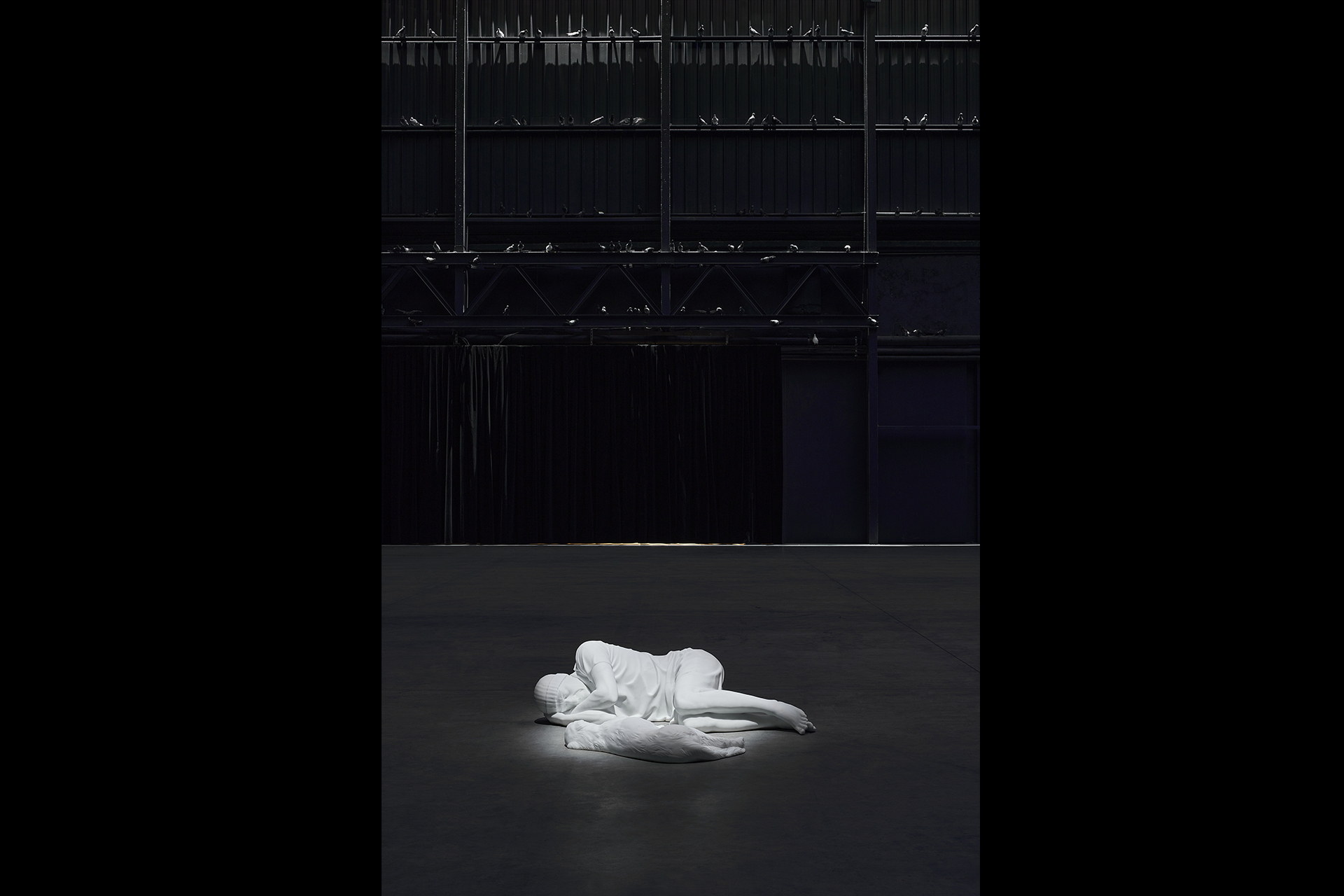

Mari’s vision has also extended to contemporary art, designing lighting for exhibitions and installations such as Breath Ghosts Blind by Maurizio Cattelan and projects for the Venice Biennale and the Triennale di Milano.

In Cattelan’s work, Mari opted for directional lighting and carved-out darkness, guiding visitors through a narrative journey that evokes suspension and introspection. In cinema, he signed the cinematography of films like One Man Up by Paolo Sorrentino and various TV productions, bringing his poetic and precise lighting grammar to the screen. His contribution to Good Morning, Night by Marco Bellocchio showcases his ability to translate theatrical intensity into cinematic language, with lighting that breathes along with the characters.

Light as ethical and poetic gesture

Since 2016, Mari has been teaching at the Silvio d’Amico National Academy of Dramatic Arts. He recently published Dire Luce, a dialogue with scholar Cristina Grazioli, in which he reflects on lighting design as a political, poetic, and aesthetic practice. The book collects thoughts matured over thirty years of work, weaving through experiences and collaborations and shedding light—literally and figuratively—on the ethical responsibility of crafting atmospheres and visions.