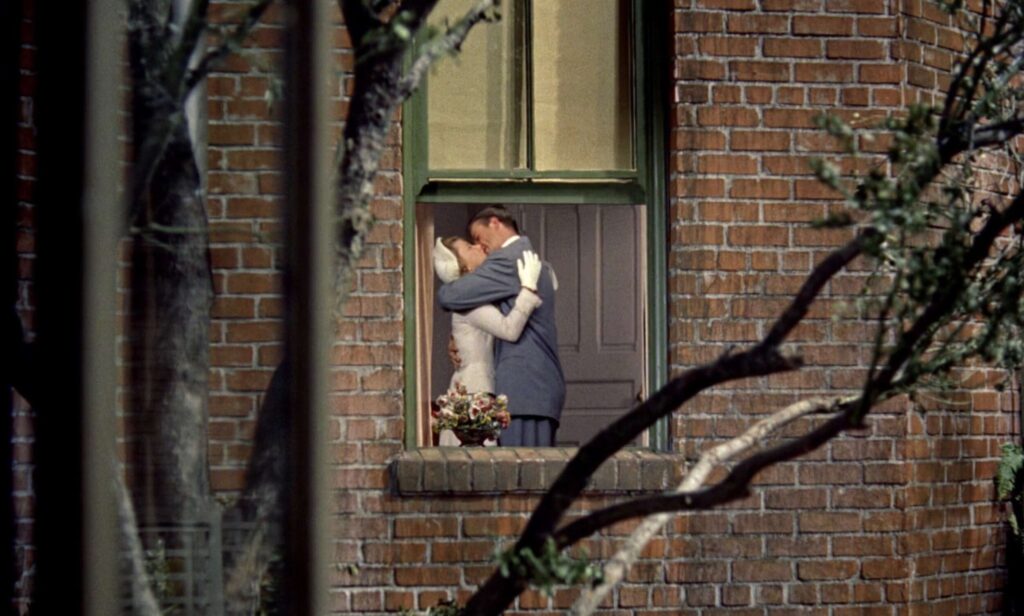

Cover photo: Vertigo (1958) – © TheMovieStore Collection

Alfred Hitchcock needs no introduction. In the 1960s, directors from the Nouvelle Vague were among the first to recognize the cultural impact of Hitchcock’s cinema, going beyond plot to examine how his films reflect on the nature of the cinematic image itself, most notably in François Truffaut’s seminal Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews. Known as the ‘Master of Suspense’, Hitchcock’s career evolved from his early British period to his American masterpieces, revolutionizing both directing techniques and narrative structure. He navigated pivotal moments in film history—transitioning from silent to sound, black-and-white to color—breaking down barriers between auteur-driven cinema and commercial appeal.

Light as a narrative device

Hitchcock transformed formal cinematic elements into storytelling tools, pioneering visual techniques that were groundbreaking for their time, like the iconic dolly zoom in Vertigo (1958). Light and color play a fundamental role in his filmography; for Hitchcock, lighting was a signature of his style. By directing the viewer’s gaze, it shaped perception and imposed specific narrative interpretations. This is particularly evident in how he handled the shift from black-and-white to color: high-contrast light and shadow dominate his earlier work, exemplified by the iconic shower scene in Psycho, while his color films, like Vertigo, imbue light with emotional resonance.

Rear window: When light builds suspense

To understand Hitchcock’s use of lighting, Rear Window (1954) is a perfect case study. The film embodies Hitchcock’s visual poetry and precise lighting direction. Rear Window is a metaphor for cinema as a window onto the world. The protagonist, L.B. “Jeff” Jeffries—a successful photojournalist—is confined to his apartment after breaking his leg. Immobilized, he starts observing his neighbors through a window using a telephoto lens and binoculars. On one hand, Jeffries holds a privileged viewpoint; on the other, he remains distanced from the action, mirroring the audience’s perspective in a theater.

He’s locked in place, and everything he knows comes from what he sees. Light filters through the windows, each neighbor bathed in their tonal hue. Intimacy is rendered in chiaroscuro, and shadows become visual metaphors for doubt. In this film, light obscures as much as it reveals, amplifying the suspense.

Shadows, Contrast, Color: Hitchcock’s Lighting Techniques

To achieve all this, Hitchcock developed a distinctive set of lighting techniques that helped define his cinematic language. One key method is chiaroscuro contrast, used to heighten suspense and emotional tension. In Hitchcock’s films, shadows are never incidental—they suggest hidden threats or unsettling emotions. Lighting can shift dramatically to alter the emotional weight of a scene. Some effects are overtly theatrical. Grace Kelly, a frequent leading lady in his films, is often stylized with swirling colored lights behind her, as seen in To Catch a Thief (1957)—highlighting her presence in a visually heightened, almost surreal atmosphere.

Hitchcock and light: a visual Language that both disturbs and delights

Light in cinema is never neutral, and Hitchcock’s work exemplifies the magic the camera can wield as a tool for emotional and artistic inquiry. As Federico Fellini once said, “If cinema is image, then light is the essential factor. In cinema, light is idea, emotion, color, depth, atmosphere, style, narrative, poetic expression”. Hitchcock understood this deeply, using light as a language that speaks directly to the viewer’s emotional core. He turned illumination into a narrative force—one that disturbs, seduces, and reveals all at once.