Cover photo: Lost in translation – Focus Features

Cinematography in Sofia Coppola’s films is a lexicon of tragic fluorescences. Between fluo backlighting, dissolving blush pinks, and night glows that feel like they escaped from a forgotten funfair, from Lost in Translation to The Bling Ring, via Marie Antoinette, we discover a universe of melancholy pop icons suspended in cosmic voids.

Every color — from candy pastels to electric neons — becomes an emotional surface, a filter that blurs glamour with isolation. Coppola’s style becomes a luminous grammar that doesn’t redeem but suspends, like a rainbow trail leading her characters straight into the abyss. Her antiheroes are unmistakable: they almost always appear drenched in playground-like, blinking, fluorescent hues.

Light is never merely aesthetic, but an emotional language that sets the rhythm of her solitary souls. Coppola’s cinematography turns hotel rooms into transparent aquariums, gilded palaces into cages, lavish mansions into glowing sets, and the faces of her protagonists into liquefied silhouettes. In these films, light becomes narrative: blinking, languid, saturated, it builds the subtle unease that pulses behind the pop sheen. This lighting-by-opposition reveals the void behind the sparkle.

Fluo and neon light in Sofia Coppola’s films: Lost in Translation and The Bling Ring

You can’t speak of Coppola’s cinema — of (back)light and color — without starting from Lost in Translation, one of the first masterpieces of postmodernity. At its center, a chandelier-city, portrayed so poignantly and exquisitely that it became the embodiment of how we, as Westerners, imagined — and still imagine — Tokyo.

Lost in Translation changed our way of being absorbed by the screen and of experiencing the melancholy of major cities. Coppola’s Tokyo is a constellation of neon signs that turn night into an artificial day. In this luminous urban space, tragic fluorescences wrap around Charlotte and Bob like mirrors, with flickering lights that dazzle and empty them, exposing their inner disorientation. In that sea of signage, intimacy becomes impossible: the chandelier-city seduces, but isolates.

The photography by Lance Acord builds a color system based on sharp contrasts — violet and electric blue, orange and pink — calibrated through low exposures and luminous lenses that capture the pulse of neon. This use of light expands space, turning each frame into an emotional ellipse.

More than a decade later, in the opulent homes of The Bling Ring, the light dazzles — but doesn’t warm. The interiors are crystal tanks lit by whitish neon, spaces as perfect and empty as aquariums.

Coppola’s tragic fluorescences in The Bling Ring — a story of youth and emptiness — turn the sparkle of luxury into a sterile glow. Every light is an artifice, every shadow exposes the absence of real life.

This is glamour without breath, suspended in an eternal luminous present with a dark soul. In Coppola’s films, the brighter the lights shine, the deeper the descent into hell.

Pink and yellow: pastel photography for adolescent distress in Marie Antoinette and The Virgin Suicides

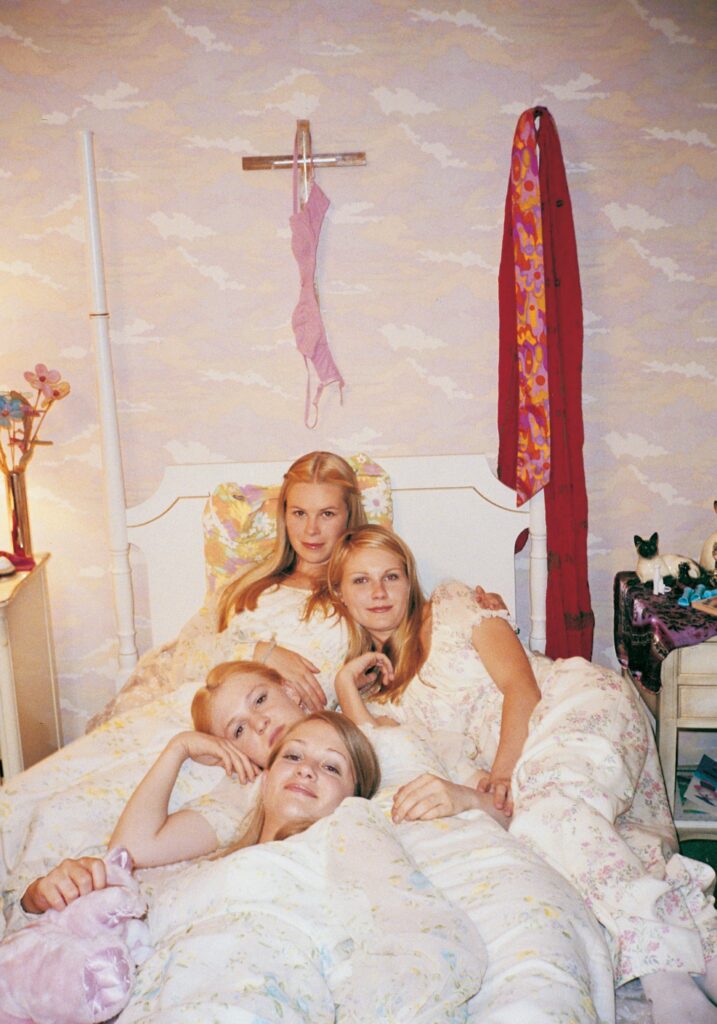

In Coppola’s visual world, one palette dominates: pink. Blush, peony, baby pink, cotton candy, pastel tones that both soothe and unsettle. In Marie Antoinette, Versailles’ salons glow like pastel music video sets, where Barbie colors promise levity but soon become a cage, a surface that veils the queen-child’s teenage anguish.

Natural light, captured with open apertures and soft filters, is compromised by artificial reflections that saturate gold and blur contours, rendering opulence as a suspended image.

An aesthetic destined for martyrdom. It’s in these moments that Burton’s true lesson emerges: melancholy isn’t a flaw, it’s an aesthetic force. A pop iconography. A universal key. He’s always turned darkness into design, and thus the outsider into an influencer.

Wednesday is a shadow that shines: she doesn’t try to match the world’s glow but recolors it with her own darkness. That’s how the different girl becomes an icon—not with reflective surfaces, but with the silent strength of shadow.

Fluo backlighting, transparencies, and veils: the Lost in Translation window scene and Priscilla’s golden cage

No amount of gold in Priscilla truly lights up the frame. With Philippe Le Sourd behind the camera and the ALEXA 35 paired with Panavision Ultra Speed lenses, Coppola pursued a digital image that was softened to resemble analog, thereby avoiding the “crispy” sharpness of modern footage.

The saffron curtains and warm lamps of Graceland are enveloped by a fluorescent backlighting that dims every reflection, turning opulence into a toxic veil.

The result is a liquid, suffocating gold, which overwhelms rather than shines, marking the emotional distance between Priscilla and the outside world.

A cinematography built on negative space and color as emotion, transforming splendor into confinement: gold is no longer luxury, but tragic fluorescence, the very matter of domestic imprisonment.

Similarly, in Lost in Translation, Coppola uses hotel windows as transparent yet impassable surfaces: Charlotte observes Tokyo through a veil of melted light, made even more fragile by the track Tommib Help Buss by Squarepusher.

It’s a brilliant moment where music and cinematography merge to render solitude transparent — a pure, liquid image, almost untouchable.

In both scenes, tragic fluorescences become the aesthetic signature enveloping the characters: a glow that doesn’t save, but intensifies their distance from the world.

In Sofia Coppola’s films, tragic fluorescences are more than a mood: they form a poetics of light that narrates emptiness and solitude through the contrast of flickers and silence. Her characters are lit like contemporary relics, wrapped in glows that amplify their fragility. Coppola exposes them, stages them, but never truly saves them from the shadow that looms over them.